By force

At the opposite, the fascist state hegemony on almost every aspect of the economy, the mussolinian corporatism with the institution in 1925 of the ENAPI (Ente Nazionale Piccole Industrie) serve the modernization of production. This Institute and the fascist bureaucracy created norms, defined quantities and strategic choices for all products.

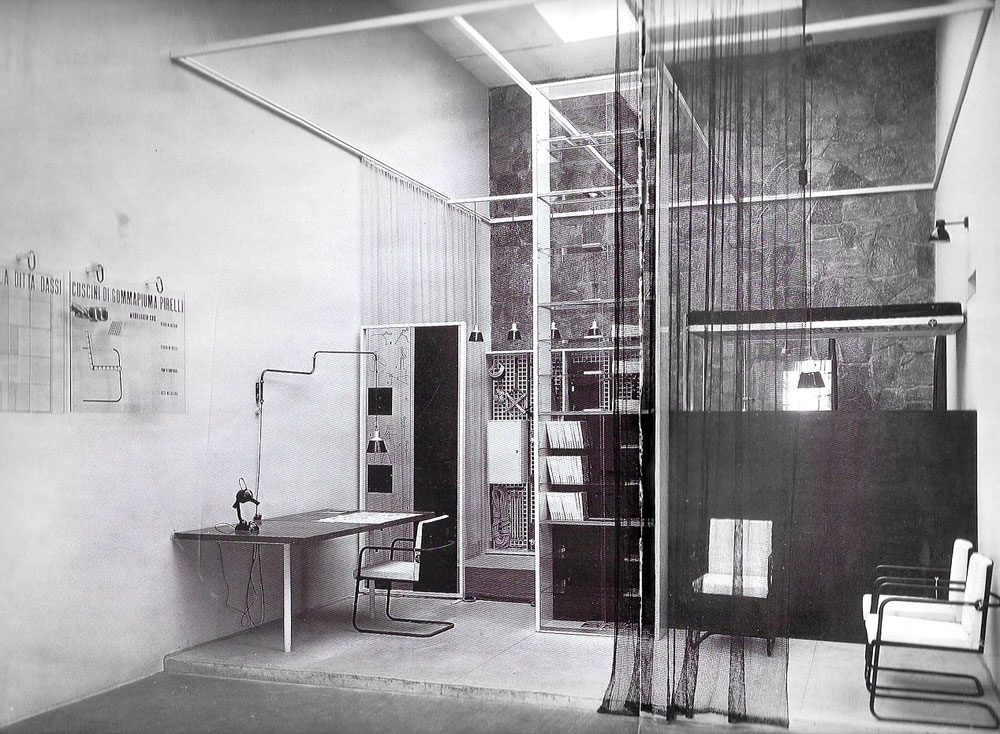

The war economy, that Mussolini adopted from the mid 30’s, is focused on autarcy. So every material that comes from abroad had to be replaced by an Italian one, even if Italian chemical industry had to invent it. Franco Albini, Ignazio Gardella, the BBPR Studio, Giuseppe Pagano, Gino Levi-Montalcini, Giuseppe Terragni, Bottoni, Asnago, Vender, Palanti and the young rationalist generation were the first to use with enthusiasm all these ersatzes and new materials: Buxus, Faesite, Suberit, Masonite, Plymax, for replacing wood, aluminium, Anticorodal, Xantal, Italian Securit glass, Linoleum, Lincrusta and neon. This effort for progress and technology in the industry was without any doubt a booster for modernity in Italy.

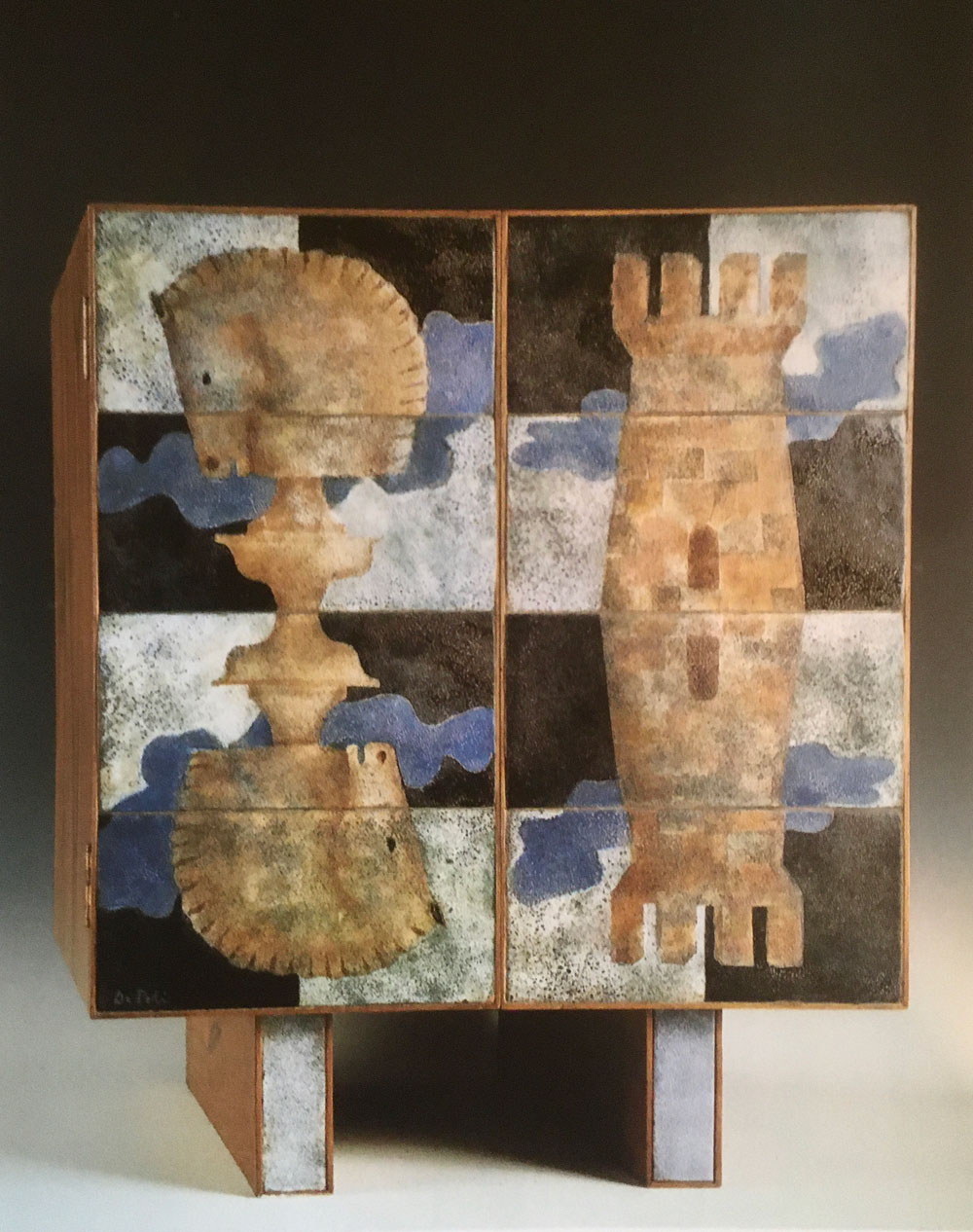

But the ENAPI was also interested in the use of domestic natural materials like travertine, marble, hay, rattan, which can be found everywhere in quantities. For instance: the Ligurian city of Chiavari has been in the first part of the 19th century the European leading production center for very light, well designed, easy chairs in wood and straw called “Campanina chair”, created in 1807 and exported since then all over Europe, until Thonet took the business after 1860 with their millions of bentwood dismountable chairs.

Reborn in the 30’s, this dying, even dead, chair industry became very popular in Italian modern furnishing, because of its modesty and simplicity, and the designs by Emanuele Rambaldi in 1933 for Chiappe-Chiavari of a range of modern models at reasonable cost were immediately adopted by the rationalists and placed as often as possible in their interiors. The nationalism of the régime (flattered by the vernacular origins of this chair), functionalism and modernity found with this resurrection a common field which has clearly participated in the modernization of Italian homes in an Italian way. This Rennaissance did not escape to Gio Ponti who made in the 50’s a redesign of this chair: the famous “Superleggera”.

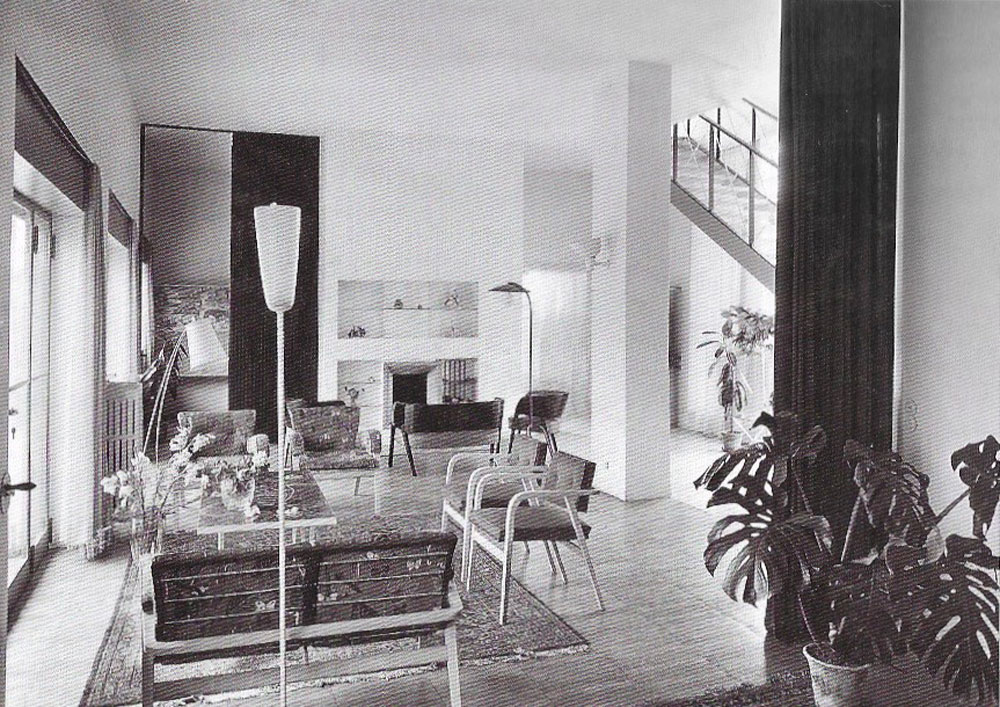

Even if these progresses were obtained by force, innovation is clearly now the condition for modernity: modernism in the 30’s and 40’s is part of the everyday life in cities: bars, restaurants, shops, public administrations and amenities are being renovated in the modern taste, sometimes homes as well…

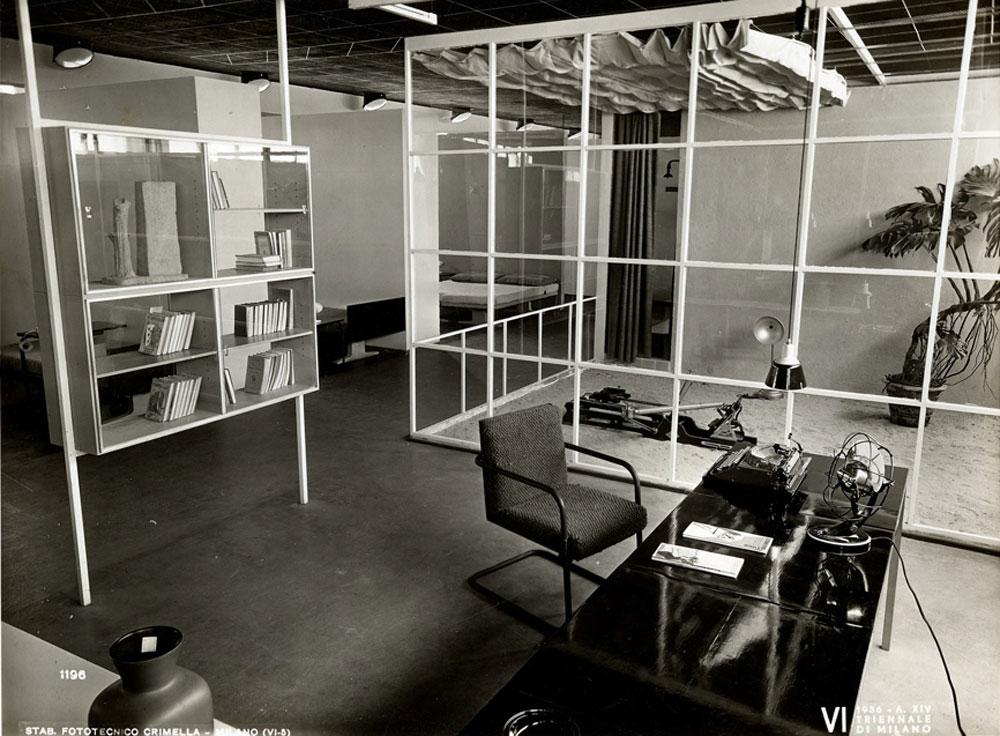

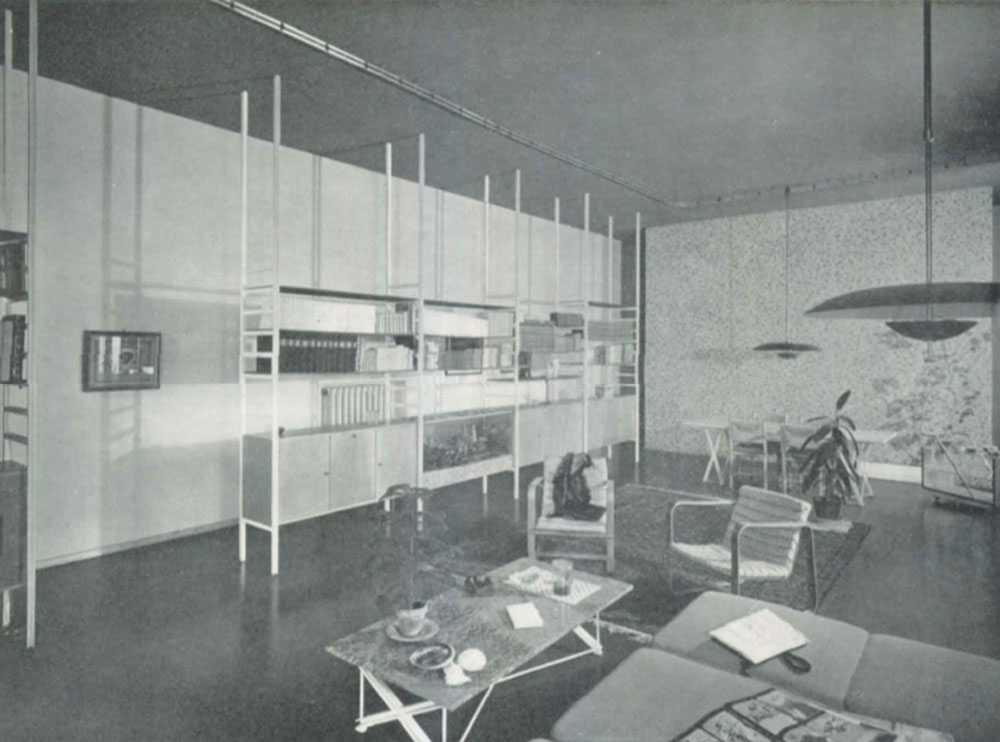

Sign of the times, the direction of Domus, the fabulous magazine created in 1928 by Gio Ponti, goes to the rationalists in 1940 and it is a rationalist architect who is chosen as the curator of the VII Triennale which in 1940 put the focus on the solutions for standard furniture.

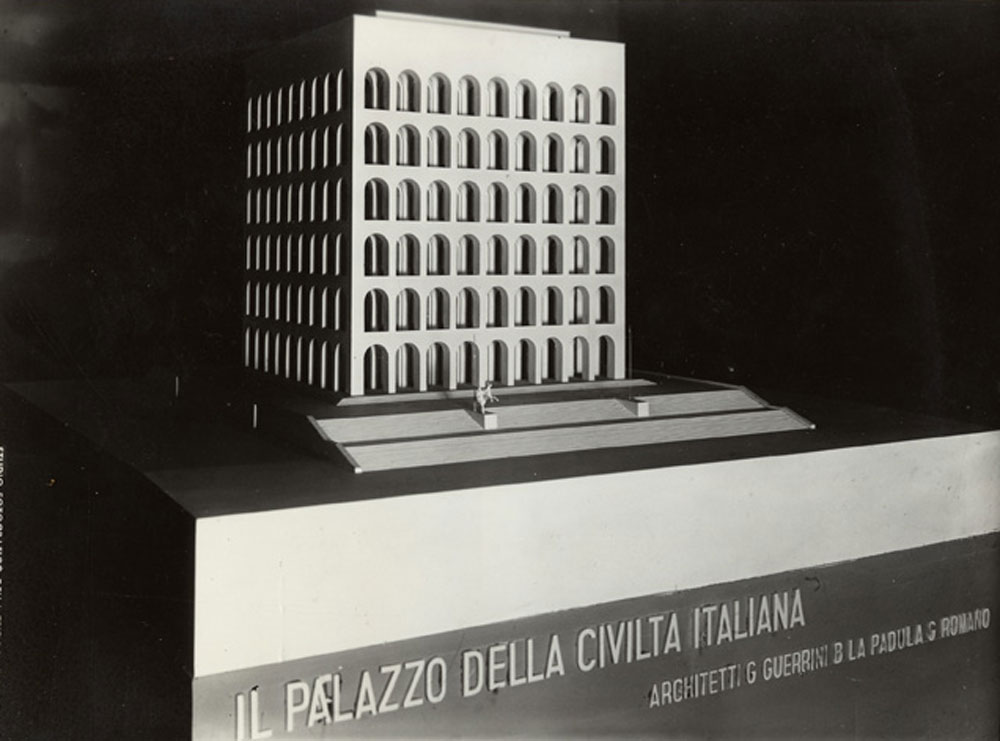

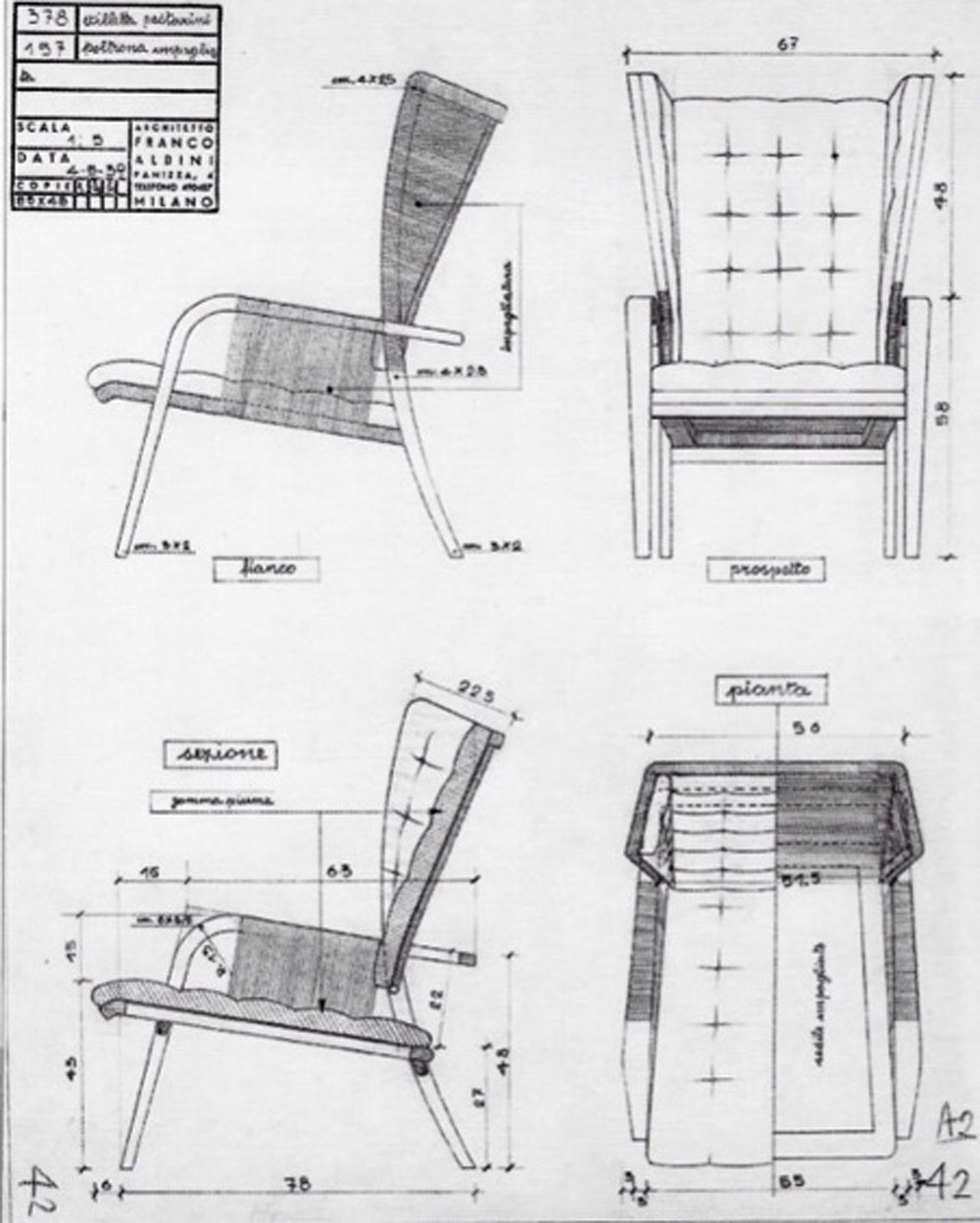

Nevertheless, rationalist architects, and in particular anti fascists like Franco Albini, are not that occupied, and if they want to participate in the building of modern Italy they have to do some compromises or concessions like Adalberto Libera in Rome for the Congress Palace of the E.U.R. 42. But they have some private commissions, and enough time to think about what is and what could be an Italian Modernity: the rationalists are working on a repertory of new types of furniture which will be very precious for the Reconstruction. They also publish catalogs of models like Giancarlo Palanti : Mobili Tipici moderni, ed. Domus, 1933.

For instance the researches about the Fiorenza chair by Franco Albini began by a first idea in the 30’s and reached their means in 1952 with the Arflex first version after almost 20 years of various prototypes and variations.